Happy Belated Free Comic Book Day, Star Wars Day, and Cinco de Mayo Tolkien Poppers!

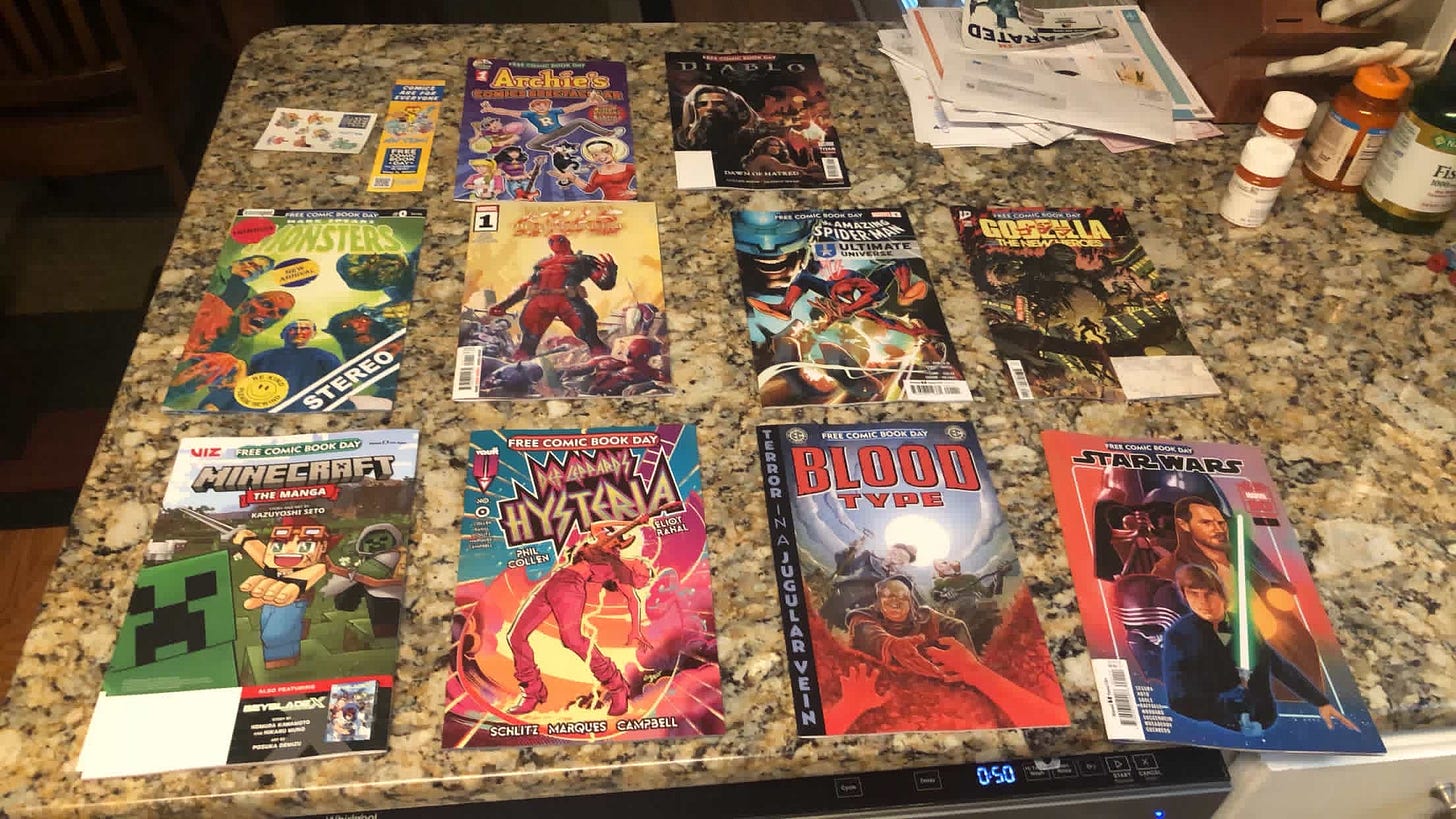

If you’re like me and celebrate all three days then you had a packed weekend. This year I decided to attend my first Free Comic Book Day at my local comic shop Rick’s Comic City in Nashville, TN. I am a huge fan of the Diablo video game franchise and saw they were putting out a new comic run and I had to get the preview! Check out my plunder and let me know if you celebrated and which comics you picked up!

I watched some Andor for Star Wars Day and went to my local Tex-Mex place for some Cinco de Mayo antics—including a mechanical bull, which I rode and absolutely dominated, naturally. But today’s post has nothing to do with either of these days or their themes! Rather, today’s post is on one of my favorite Quentin Tarantino films Django Unchained and how it utilizes myth in a similar way Tolkien did in writing The Lord of the Rings. I hope you have fun reading this and hope to hear how you spent your Free Comic Book Days, Star Wars Days, and/or Cinco de Mayos!

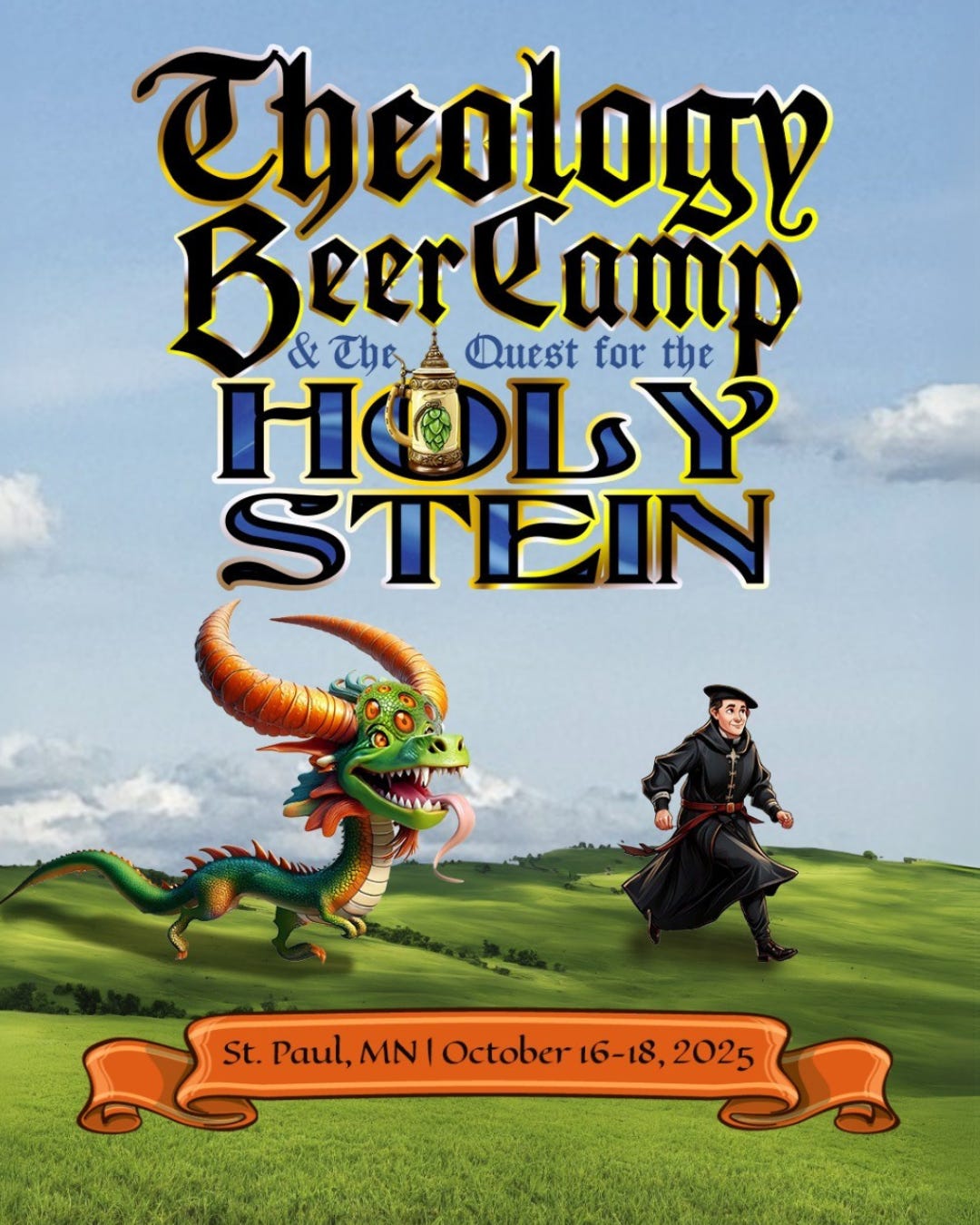

Today’s post is brought to you by Homebrewed Christianity’s Theology Beer Camp. In honor of the 50th anniversary of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Theology Beer Camp 2025 will be decked out in all things Monty Python! If you get tickets, there will also be a live Discord watch party of Monty Python and the Holy Grail tonight 8:30pm EST. Early Bird tickets end May 16th, so get your tickets today!

“History often resembles myth, because they are both ultimately of the same stuff.” (OFS, 47)

This quote from Tolkien is one of the gateways that invites us into the depths of his thinking and how he viewed the world and the stories humans make in it. Part of why his legendarium is so captivating is because of his understanding of how humans interpret the world. Discovering an ultimate and final reason to explain how and why myths emerge from history is not possible in Tolkien’s eyes. What is important is the recognition that humanity takes its knowledge and experience of the past and present to formulate stories out of them. These narrative constructs, built from the flow of time, are what hold the meaning within the implications of their composition. This applies to both history and myth.

While history and myth have different methodologies and aims, neither can exist without story and aesthetic impact. What moves people in reading great stories are usually not the tiny details such as what clothes people were wearing or the rates of exchange (although those aspects are appreciated by students of myth and history), but the qualities that people demonstrate within these tales, e.g., bravery, friendship, and love. Reverence is not the only emotion triggered through stories, but also revulsion. The evil that villains or others perform in such narratives stirs within those that read them a desire to act differently and set their lives into lifegiving motion.

For Tolkien, the prime example where myth and history truly meet is the person of Christ. He is the true hero and exemplar of both, incarnate and active:

“There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true, and none which so many sceptical men have accepted as true on its own merits. For the Art of it has the supremely convincing tone of Primary Art, that is, of Creation. To reject it leads either to sadness or wrath.” (OFS, 78)

Strong words from The Professor. Whether or not one accepts Tolkien’s religious or metaphysical claims, he believed that Christ was and is the exemplar of what it means to be the ideal human–with all the original virtues intended by God, but without loss or corruption–while also being divine. But I will stray from debates surrounding the divinity of Christ and models of God! My point here is that if Christ is the perfect example of a mythological and historical person intertwined, then, for Tolkien, people, both historical and fictional, should reflect the being and character of Christ.

Many have written about heroes in The Lord of the Rings reflecting different aspects of Christ’s person and character. The reading of Tolkien’s works through Christ’s threefold office of Priest, Prophet, and King has been performed and repeated by many. And while there have been a plethora of Marian readings of Tolkien’s women characters, very little has been written on any of these women embodying the being and virtue of Christ himself or reflecting the image of God.1 Because Christ is the hero, according to Tolkien’s faith, his fictional heroes share christological qualities that inform their acts of goodness and bravery. The willingness to lay one’s life down is shared by the likes of Aragorn, Éwoyn, Frodo, and Gandalf–along with most, if not all, of Tolkien’s heroes. Their actions are also employed for the purpose of saving others from the assault of an agent of evil.

An unlikely candidate for a position among heroes that demonstrate Tolkienian qualities is Django Freeman from Quentin Tarantino’s film Django Unchained. While Django becomes a bounty hunter and kills for revenge as opposed to Tolkien’s heroes who demonstrate compassion and the proper courtesies of war, he puts his life on the line to save his wife Broomhilda, slays orcish-like slavers and the dark lordesque plantation owner Calvin Candie, and liberates the enslaved folks at the plantation known as Candie Land. Comparing the slavers of the American South to the orcs and their leaders in Middle-earth strengthens the case that Django can be seen as a parallel to Tolkien’s own fictional heroes.

But my case for Django as a hero as the Tolkienian type is not primarily based on Django’s characteristics, but on the way in which he is thrust into his quest. The movie begins with multiple classic landscape shots typical of American Western films to then be taken to a chain gang of enslaved men being driven by two men on horses known as the Speck brothers. These brothers have recently purchased the enslaved group from Greenville that includes Django within their ranks. Upon their journey home, a man driving a wagon named Dr. King Schultz–who appears to be a dentist–crosses their path in search of Django and offers to purchase him from the Speck brothers. They don’t like Schultz and threaten to shoot him. Within seconds, Schultz shoots one brother and the other’s horse, causing it to fall on him and break his leg. Rather than being a dentist, Schultz turns out to be a gunslinging bounty hunter. He unchains Django, commands him to take the dead brother’s jacket and his horse, and provides the rest of the chained men with the keys to their shackles, encouraging them to take their freedom.

As Django and Schultz ride off, Django learns more about Schultz’s occupation by shadowing him in real time. During this scene of comedic and succinct bounty hunting from Schultz, he tells Django that he needs him in order to identify three brothers who are wanted for murder and are plantation workers. Further, he offers Django his freedom and a cut of the reward if he successfully helps Schultz. Django agrees and they set off to Tennessee in search of them.

Along the way to Tennessee, Django reveals that he is married to a woman named Broomhilda, that she was raised by German immigrants, and speaks German. Schultz, who is German, is absolutely stunned by this fact and reveals that Broomhilda is a famous character from a German legend. After a successful execution of the wanted men in Tennessee and local leader of the KKK, Schultz tells Django an extremely summarized version of the story of Brünnhilde and Siegfried. Based on the Poetic and Prose Edda, Schultz tells the story of how Brünnhilde disobeys Wotan (Odin), is placed on top of a mountain surrounded by a ring of fire, and Siegfried rescues her. For Schultz, this story evokes a strong connection to his self-understanding as a German and tells Django that he will help him rescue Broomhilda from whatever plantation she may be imprisoned in. Django asks why and Schultz says that meeting a real-life Siegfried is a pretty big deal and feels compelled to help him.

For Schultz, what he sees in Django is the myth of Siegfried and Brünnhilde living and breathing right before him–the meeting of myth and history. Not only is this feeling of a secondary world manifest reflective of Tolkien’s own articulation of the feeling of being absorbed into the story world, but Tolkien’s take on the Incarnation of Christ, making Django both a Tolkienian and Christological figure.

Now, Django Unchained takes place in 1858 and the version of the story of Brünnhilde that Schultz tells is the rendition written and popularized by Richard Wagner in his The Ring of the Nibelung also known as the Ring Cycle, of which the first part was performed in 1869. So, the timeline is a little off pertaining to Schultz's ability to tell that version of the story to Django. Additionally, Wagner’s Ring Cycle was commandeered by Hitler by utilizing Wagner’s antisemitism to construct a nationalistic identity based on a mythological past rooted in Norse mythology, making its parallels to Django’s story a little odd. However, Tolkien was inspired by Norse mythology and expressed his dislike for Wagner’s take on it. Regardless, there is scholarship to support that Tolkien continued to dialogue with Wagner in his thought process in writing The Lord of the Rings in a way that challenged and attempted to do something creatively different than Wagner.2

This line of reasoning related to Tolkien’s own engagement with Wagner fits within Tarantino’s narrative frame for Django Unchained. Rather than making the cowboy of traditional Westerns a white macho man that embodies a mythological and nationalistic past, Tarantino gives this role to Jamie Foxx (who plays Django) and paints a more historically accurate picture of the reality of the United States in the 1800s, highlighting the ugliness of slavery and other forms of systemic racism. The enslaved rather than the defender of slavery is the cowboy, who becomes free, defeats those who benefit from institutional racism, and frees those who have also suffered from its evil. Tarantino engages with traditional Western movies to revise them and create something that subverts their narrative norms. Both Tolkien and Tarantino work with complicated and, in many cases, problematic sources to bring about something better for their audiences.

After the moment of Schultz’s realization of myth come to life, Django becomes Schultz’s partner in the bounty hunting business, discovers that Broomhilda is being held at the plantation of Calvin Candie aka “Candie Land,” successfully makes it to Candie Land, kills Candie, rescues Broomhilda, kills all of those in Candie’s service, and frees all those enslaved at the plantation.

In my estimation, Django’s actions resemble those of Tom Bombadil’s saving of the hobbits from the Barrow-wights in the Barrow-downs; Aragorn at the Battle of Pelennor Fields when he arrives in the ships of Umbar to assist Rohan and Gondor in their battle against the army led by the Witch King; and Frodo, Sam, Pippin, and Merry’s saving of The Shire during “The Scouring of the Shire.” There are many more parallels that can be made, but I will leave the reader to make these other connections on their own.

One of the main aspects that Django shares with the heroes in Middle-earth is that at first they seem mundane in their initial appearances both to the audience and the other characters, but are later revealed to be mythological heroes incarnate. When Merry and Pippin encounter the Rohirrim after the Battle of the Hornburg and the Battle of Isengard, Théoden and the other Rohirrim are dumbfounded. For them, they believed hobbits to be legendary, existing only in fables and stories:

“‘It cannot be doubted that we witness the meeting of dear friends,’ said Théoden. ‘So these are the lost ones of your company, Gandalf ? The days are fated to be filled with marvels. Already I have seen many since I left my house; and now here before my eyes stand yet another of the folk of legend. Are not these the Halflings, that some among us call the Holbytlan?’

‘Hobbits, if you please, lord,’ said Pippin.” (TT, 727)

This meeting of the history and legend within the bounds of Rohan leads to the destruction of the Witch King and the restoration of the realm of Gondor and Rohan.

Pertaining to Aragorn’s legend, he is descended from the line of Númenóreans after they fall away from prominence and into the obscurity of past legend, where the alleged return of the king of Gondor has been so far unfulfilled that to look for or believe in a returned king would be to totter towards ignorance or insanity. Before Aragorn took the throne in Third Age 3019 the last king was Eärnur in T.A. 2050, almost a thousand years before Aragorn’s birth. Further, Aragorn wanders in the wilderness with the other descendents of Númenor, the Dúnedain as rangers, pushing their lineage and doings in the world on the outskirts. This reality sheds light on Denethor, Steward of Gondor’s reaction when he learns about Aragorn’s progress towards Minas Tirith. Denethor descends from a long lineage of ruling stewards and when a prophesied king emerges to fill the throne he and his ancestors have been occupying for a millennium, it is understandable why he is skeptical and generally resists Aragorn’s claim of kingship. However, Aragorn arises from history, poorly perceived in mundanity by others, and breaks into it, enchanting the world with the residue of myth that his actions leave behind.

Like Aragorn and the hobbits, Django arises as a mythological hero within the fictional historical context of Django Unchained, but also one for our own day and age. The hobbits can teach us to fight for those we love, Aragorn can show us what it means to be brave and a healer, and Django can move us to seek out the mythological-historical milieu in which we live to sit in it and interrogate it in a way that renews how we view and act in the world.

Django’s gunslinging, foul language, and 19th century American perspective would probably not fit within the characteristics of a proper hero for Tolkien, but the way in which he moves those within the film and without through his mythological merging into history as well as his heroic actions to face evil, fight for those he loves, and free his enslaved neighbors puts him in the running with the likes of Túrin, Beren, and Samwise.

One of the few pieces of scholarship that take this approach is Christine Falk Dalessio’s “‘Her Heart Changed, or At Least She Understood It’” in Estes, Douglas, editor. Theology and Tolkien: Practical Theology. Lexington Books/Fortress Academic, 2023.

McGregor, Jamie (2011) "Two Rings to Rule Them All: A Comparative Study of Tolkien and Wagner," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 29: No. 3, Article 10. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol29/iss3/10.

My book Tolkien and Pop Culture: Volume I is now available! This book is a selection of my Substack posts from the past couple of years, cleaned up, and formatted for publication. For the first time, you can get all these essays in print or in your Kindle library. It’ll look great on your shelf and be available for your own Tolkien purposes! Use the QR code, the link, or direct message me to order your copy: https://a.co/d/eBE7jiH